FROM FOLKESTONE TO THE FRONT

Folkestone played a vital role in WWI as a port through which 10 million troops, labourers and ancillary services would depart for France or return either on leave or for treatment of wounds. Amongst this number were the CLC, who would have arrived by train from Plymouth or Liverpool after a long sea passage across half the globe.

A Belgian paddle steamer discharges soldiers at Folkestone Dock

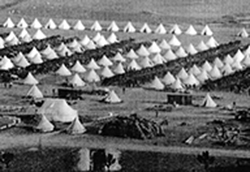

On arrival at Folkestone, they stayed at the Labour Concentration Camp, a tented camp set up in April 1917 under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel F. Hopley at the foot of Castle Hill beside Cherry Garden Avenue.

Tented camps were the CLC stayed

Their existence was little known by local residents, as they were closely supervised and could not leave the confines of the camp without an escort. The compound could accommodate only 2,000 “Chinese and Kaffirs” (- the latter referring to labourers who had been recruited from South Africa), but the CLC built a second enclosure of reinforced concrete hutments in the summer of the same year. According to a note in Folkestone During the War, 1914-1919, by Dr. J. C. Carlile, “Cherry Garden Camp, as it came to be called, was really two separate blocks, with kitchens and hospitals. It could comfortably house 1,500 men.”

Concrete huts built by the CLC (to right of photo)

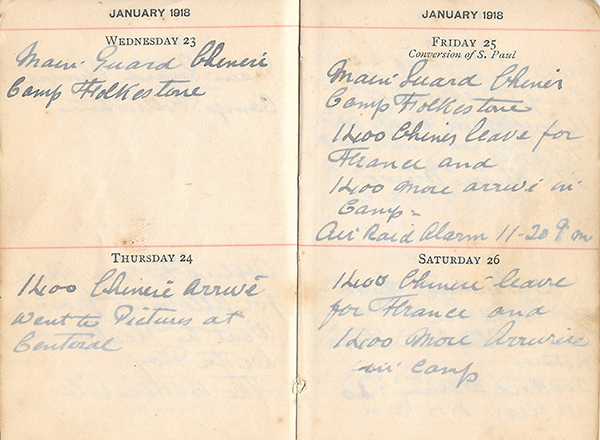

The extra accommodation had become a necessity. The movement of labourers to mainland Europe became increasingly urgent towards the end of 1917 and beginning of 1918. A diary kept by William Snook from 61st Company of the Royal Defence Corps, who was on guard duty at “the Chinese Camp”, clearly shows that the labourers would arrive - sometimes on consecutive days - in batches of up to 3,000, stay overnight and leave the next day for France.

Diary of William Snook, guard at the Chinese Camp, showing CLC arrivals and departures

A steady number of 2,000 or so Chinese were kept in Folkestone to do manual labour at Shorncliffe Army Camp, work in the nearby military hospitals or help with loading and unloading at the docks. Michael Summerskill, author of China on the Western Front, mentions a resident remembering some of the men going to work on a requisitioned fairground engine.

Shorncliffe Hospital, where some members of the CLC worked and others were hospitalized

The men could not stray far, but in whatever spare time they had, they would make sure to obtain a reminder of their visit to Folkestone. Local historian Peter Bamford recalls the owner of photography studio H. B. Green in Cheriton telling him that some of the men would have their photograph taken, holding an alarm clock purchased from Suttons the Jeweller’s. The photos were to be sent home as a souvenir of their sojourn and the clock, with its distinctive bells on either side, was probably proof of their foreign environs. Sadly, none of these photographs have come to light.

Folkestone would be the last safe haven for the men before their departure to France. They would have looked forward to the prospect of finally earning good money for labour that would be relatively easy for them; after all, they were used to heavy physical work as farmers back in China. What they could not expect, however, was a war of a scale and brutality beyond imagination, awaiting them only hours away.

Cecil Harcourt Lees describes his first encounter with Chinese labourers while crossing the English Channel. He himself was later assigned to the CLC.

“On my first war-time crossing of the Channel, among the ships of the convoy were two steamers from whose upper decks multitudes of strange folk looked across at us. They were all dressed alike in long, loose-fitting cloaks of ruddy brown material, and they wore little caps with cat-flaps not unlike those donned by our airmen when aloft. Their hair was jet black, their strange, expressionless' faces berry brown. They were Manchurians nearing the land of war to give their labour to the cause of Britain—for a sound, commercial consideration be it premised.

At that time one had heard vaguely about “Chinese labour”, but here was its embodiment in these two shiploads of grinning Orientals, who looked so curiously alike that one seemed to see the same man a hundred times over. ... I was to see more of these far-travelled Children of the Dawn in my next day's journey, as I had arranged to visit the main camp, where they are received and whence they are drafted to the sectors where their labour or their craftsmanship is most required.

Few things that I have seen in the British zone impressed me more favourably with the British genius for organisation than the handling and bestowal of these Chinese labourers... Figure what it means to sign a contract for three years' work at a place over six thousand miles away from your home!”

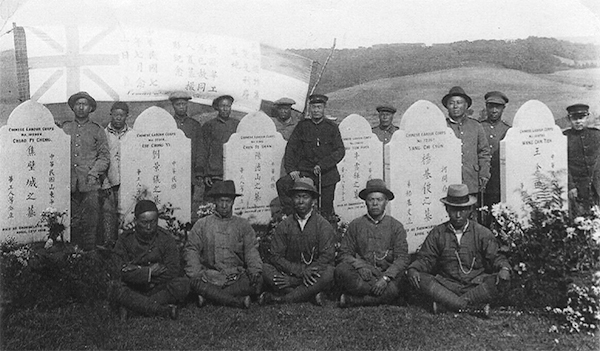

CLC members buried in Shorncliffe Military Cemetery

Each headstone is engraved with three columns of Chinese characters which should be read from top to bottom. The central column reads: Grave of xxx. The right column indicates where the labourer originated from, although in most cases, it merely reads “Republic of China”. Apart from one headstone, the characters in the left column read “Jointly erected by Chinese labourers”.

| CLC no. 72367 Yang Jijun (Yang Chi Chun), from Hejian City, Hebei Province, d. 30th April 1918 at Shorncliffe Hospital of purulent bronchitis (Spanish ’flu). His headstone reveals that it was erected by his younger brother Yang Jiwen. It was not unusual for multiple members of the same extended family to join up for the CLC. |  |

| CLC no. 109761 Wang Jintian (Wang Chin Tien), from Anyang County, Henan Province, d. 4th April 1918 at Shorncliffe Hospital of purulent bronchitis (Spanish ’flu). |  |

| CLC no. 24640 Niu Yunhui (Niu Yun Huei), d. 2nd July 1917 at Shorncliffe Hospital of tuberculosis. |  |

| CLC no. 11916 Chen Deshan (Chen Te Shan), d. 30th August 1917 at Shorncliffe Hospital of tuberculosis. |  |

| CLC no. 37614 Liu Jingyi (Liu Ching Yi), d. 1st January 1918 at Shorncliffe Hospital of tuberculosis. |  |

| CLC no. 105994 Jiao Bicheng (Chiao Pi Cheng), from Pingdu County, Shandong Province, d. 13th April 1918 at Shorncliffe Hospital from intestinal obstruction and toxaemia (septicaemia). |  |

Chinese labourers beside the graves of their fellow countrymen at Shorncliffe Military Cemetery. The man standing third from the right is possibly the brother of the deceased person named on the headstone to his right.

Commemoration Service on 14th March 2018 at Shorncliffe Cemetery

Shorncliffe Cemetery lies surrounded by woods on a gentle slope overlooking the English Channel. On the day of our commemoration ceremony on 14th March 2018, the entire hill was bathed in the warm glow of a spring afternoon. As a procession of young people led by a piper from the Royal Gurkha Rifles emerged from the dip of the cemetery to the soulful tune of Flowers of the Forest, the scene could not have been more stirring.

Candles and wreaths were laid before the graves, followed by speeches by the Mayor of Folkestone Cllr Roger West, and Sergeant Major Martin Dunn of Shorncliffe Station.

It was perhaps the young participants, though, who made the most moving tributes. “Oh Lord, Hear My Prayer” rang through the air, as pupils from Christ Church CEP Academy sang beside the headstones. Then two students from Earlscliffe College recited Nostalgia(乡愁), written by Chinese poet Yu Guangzhong (余光中) in his latter years when reminiscing about the homeland he had left behind. The poem could not have been more fitting for the men whom we were commemorating that day:

Nostalgia

When I was a child,

Nostalgia was a tiny postage stamp,

I, on this side,

My mother, on the other.

When I was older,

Nostalgia became a slim boat ticket,

I, on this side,

My bride, on the other.

Later,

Nostalgia was a squat tomb,

I, outside.

My mother, inside.

And now,

Nostalgia is a shallow strait.

I, on this side,

The mainland, on the other.

乡愁

小时侯 乡愁是一枚小小的邮票

我在这头 母亲在那头

长大后 乡愁是一张窄窄的船票

我在这头 新娘在那头

后来啊乡愁是一方矮矮的坟墓

我在外头 母亲在里头

而现在 乡愁是一湾浅浅的海峡

我在这头 大陆在那头

Photos courtesy of: Peter Tunbridge, Peter Hooper, Peter Bamford, Alan Taylor, Vince Williams, Gregory James.James Brazier, Kahfei Ho and Andy Smith.

Other archive photos taken from the internet